In a recent meeting I observed an interesting discussion about the fairness of subsidies. One person pointed out that Chinese domination of energy technology manufacturing – solar, wind, batteries, electric vehicles – was in large part due to both present day subsidies and subsidies in the past. Another participant responded that you could say the same of the USA and various digital technologies. The iPhone is as much a product of public funding as swashbuckling entrepreneurial genius. Almost every technology that makes the iPhone so smart traces its funding back to a public agency in the US government. Over a coffee break the group agreed that there is no such thing as pure unadulterated competition between private sector firms.

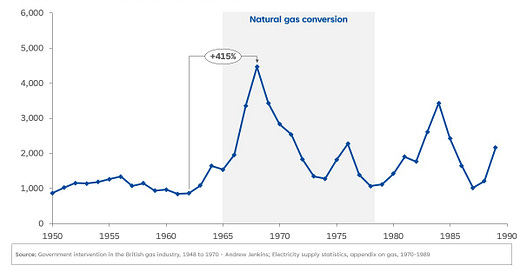

Similarly, there is no such thing as pure unadulterated competition between technologies. Consider heating. Various commentators complain that heat pumps are being subsidised. However, the gas boilers that heat 78% of British homes are also the product of decades of massive state subsidies. Today’s boilers run on natural gas. However, before the 1960s Britain’s gas system couldn’t accommodate natural gas. It had been built for town gas (gas made from coal) with a different chemical composition. Between 1966 and 1977 the state-owned British Gas Corporation executed one of the most remarkable mega projects in history, natural gas conversion. 35 million appliances were replaced or retrofitted in 13.4 million customer homes. A vast gas transmission pipeline network was constructed. Regional gas distribution networks were also rebuilt to accommodate natural gas. There was no direct cost for the end consumer. The whole programme was subsidised. The state covered a portion of the costs through general taxes with the rest spread over all gas consumer bills.

Heat pump conversion is just one part of the energy revolution. It is something of a cliché to say that Britain faces a ‘once in a generation’ infrastructure programme. So how did the last generation to attempt anything like this do it? Between 1947 and 1979 a generation of engineers oversaw a ridiculous number of mega projects in energy; nuclear, the supergrid, LNG development, gas conversion, Scottish hydro, rural electrification, and many more. How did the post-war energy system builders pay for all this?

After the second world war the gas and electricity industries were brought into state ownership. Electricity in 1947 and gas in 1949. Both industries became independent public corporations answerable to government but not in the civil service. Corporation accounts were separated from national budgets, with the aim of reducing Treasury interference and encouraging autonomy and innovation. The corporations had two main objectives: to act in the public interest and to breakeven over a period (meaning they could ‘take one year with the next’). It is worth emphasising that the nationalised industries were not in the public sector as we mean it today. They were commercial state-owned enterprises. Their output wasn’t offered for free, as is the case with the National Health Service or schooling.

The nationalised energy industries had three income streams to pay for investments: borrowing, bills, funding from the state.

In the first decade after the war both gas and electricity directly raised fixed interest stock, but stockholders had no voting rights and did not own equity.[1] Between 1948 and 1955 the British Electrical Authority did six raises, each between £100 million and £200 million (between £2.5 Billion and £5.0 Billion in today’s prices) with returns of 3% to 4.5%. After 1955 all capital was raised by the Treasury.[2] The Gas Council was given more freedom and was permitted to borrow up to £1,200 million from 1965 on its own balance sheet (£20 Billion in today’s prices), raising fixed income debt with a Treasury guarantee.[3]

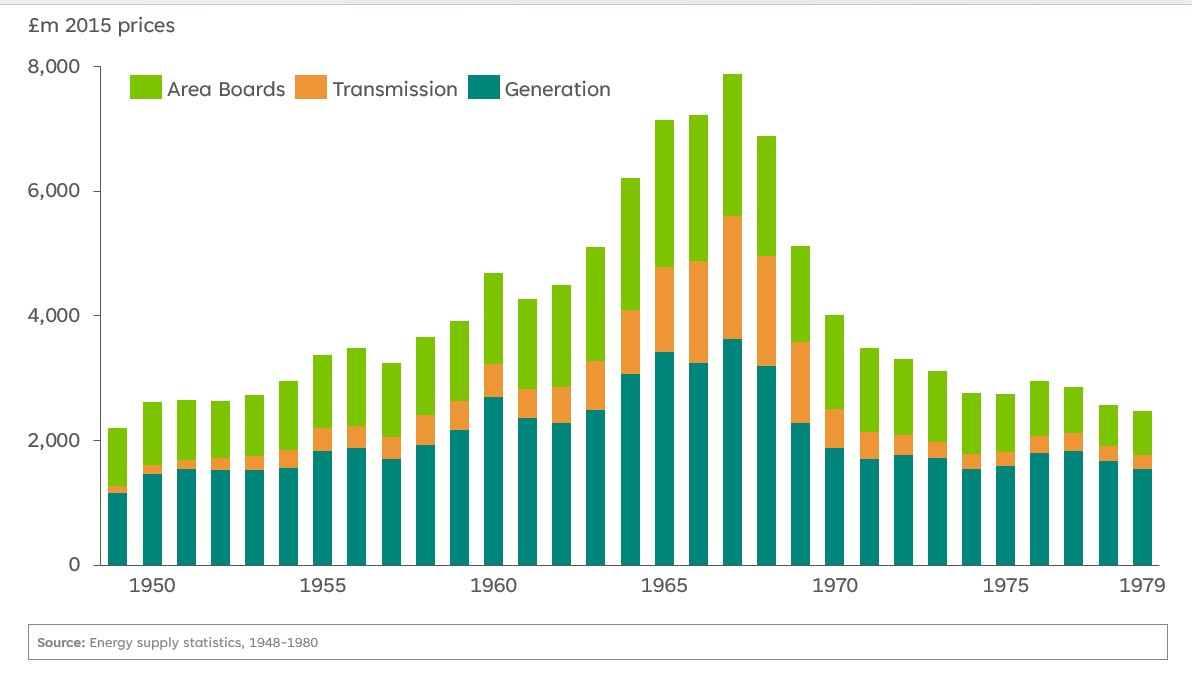

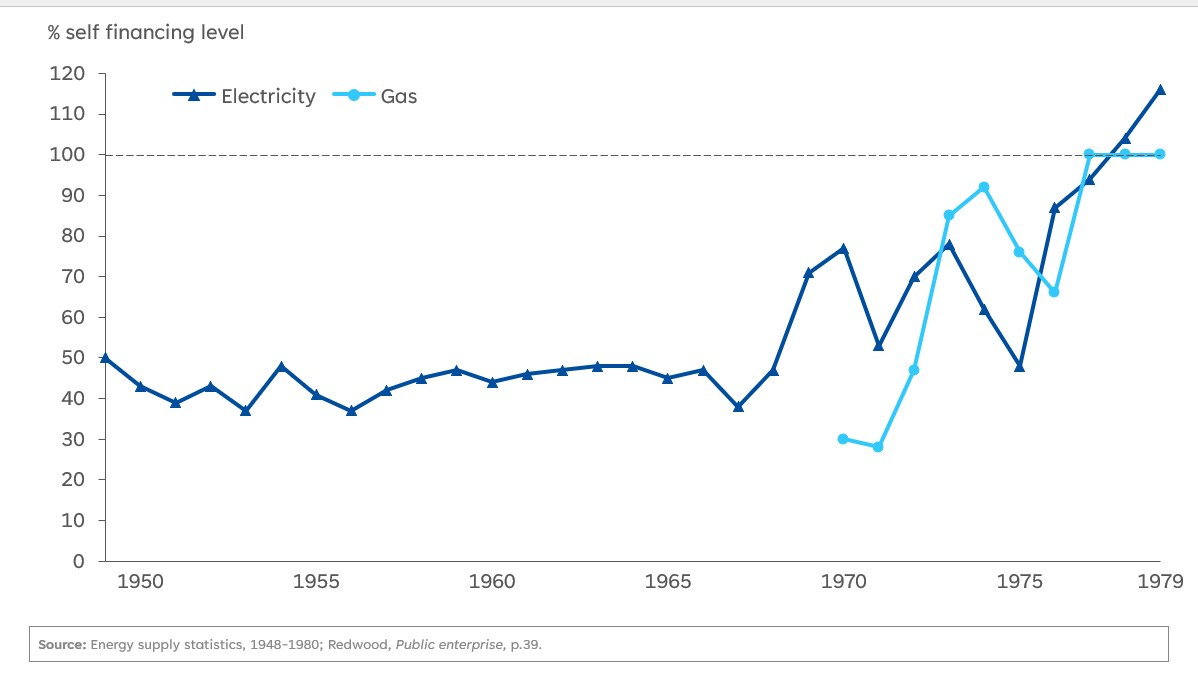

Another way to pay for capital investments was from consumer bills. The percentage of investment paid for from bills was called the ‘self-financing’ ratio. The final route was funding from the state. The Treasury could fund through transfers, loans or fixed interest stock issues (guaranteed by the state). A key feature of this financing arrangement was the low cost of capital. The state could borrow money at a lower cost of capital than private sector firms could. This meant the nationalised energy industry could undertake projects with very long or uncertain paybacks – like building networks, nuclear, and hydroelectric.

The economist Dieter Helm has characterized the approach as ‘pay-as-you-go’. The post war generation paid for investment out of current income. The only question was whether to ask citizens to pay as consumers or taxpayers. Paying from consumer bills was regressive because all citizens paid the same price regardless of income level. Paying from tax was more progressive as the rich bore a higher share of the cost.[4]

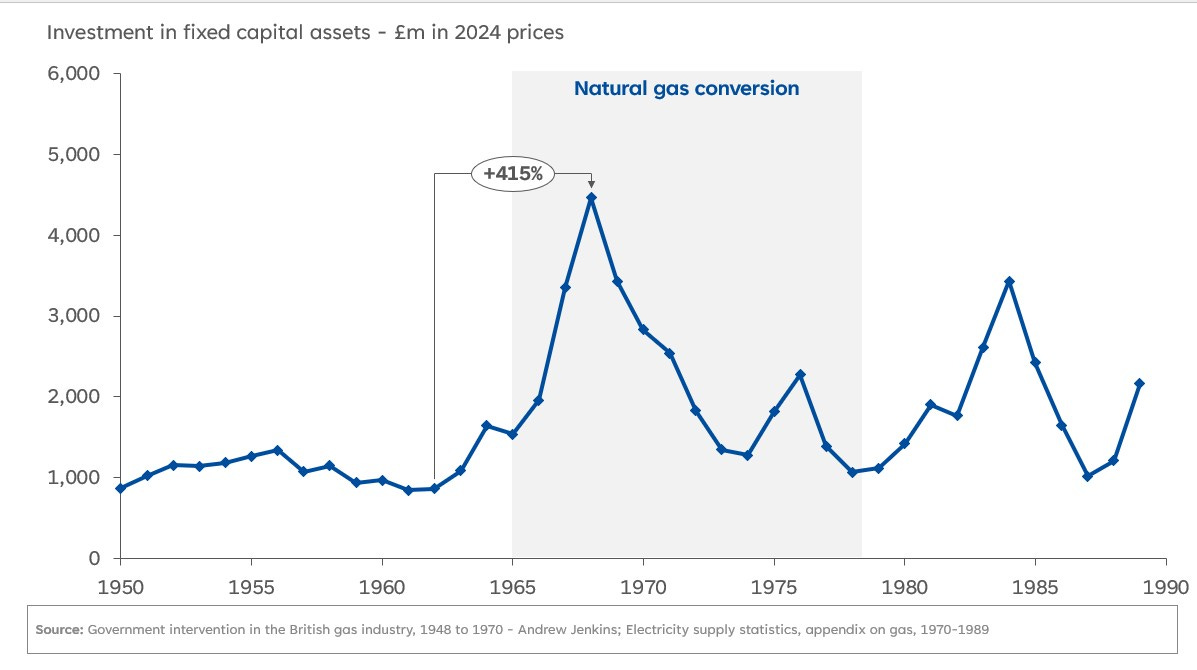

Pay-as-you-go was a simple, transparent and flexible approach. In a build phase the self-financing levels were held low to hold down customer bills. Once the assets were built the self-financing levels were raised. As figure 1 shows in gas investment increased dramatically over the late 1960s and early 1970s due to the gas conversion programme. In 1970 the self-financing ratio was just 30% (sadly I don’t have data for before this). Once the programme was completed the self-financing ratio was raised to 100% in 1977, 1978 and 1979. It was the same story in electricity. Capital investment grew between 1950 and 1967 and then steadily fell. The self-financing ratio hovered between 40% to 50% until 1968 before being cranked up to 115% in 1979, meaning that the industry was paying back into the treasury.

Figure 1: Gas industry investment 1950-1989.

Figure 2: Electricity industry investment, 1950-1979

Figure 3: Self financing level for the gas and electricity industry, 1950-1979

Pay-as-you-go was a suitable funding mechanism for a generation of politicians and engineers that saw it as their obligation to build an endowment for future British citizens. This may seem counterintuitive. On the surface a ‘save then spend’ approach may seem more prudent. But as the economic historian Avner Offer lucidly explains ‘governments succeed where markets fail because they do not commit to long-term contracts… A financial balance is a hoard. Once spent, it is gone…. Pay-as-you-go is a claim on the community’s indestructible real tax base. In effect, it is a claim on a share of GDP - how much to be revealed when it becomes due for payment.’[5]

[1] Foreman-Peck and Millward, Public and private, p.296.

[2] Hannah, Engineers, Managers and Politicians, p.53.

[3] Williams, A history of the British Gas industry, pp.231-33.

[4] Helm, Energy, the State and the Marker, p.25; Dieter Helm, ‘Energy network regulation failures and net zero’, 5th January 2023, Helm’s website.

[5] Avner Offer, ‘The Economy of Obligation: Incomplete contracts and the cost of the welfare state’, Discussion Papers in Economic and Social History, No 103, August 2012.

This is super interesting Arthur.

Do you know if anyone has ever compared the cost of the current subsidies for private electricity producers and infrastructure owners, vs what it would cost the taxpayer if we built a publicly owned electricty system, operating in a similar way to the one you've described here?

Great post Arthur - pedantic accounting point incoming. Here "...nationalised energy industries had three income streams to pay for investments: borrowing, bills, funding from the state." Not income but sources of capital or cash flow. Only the bills were income